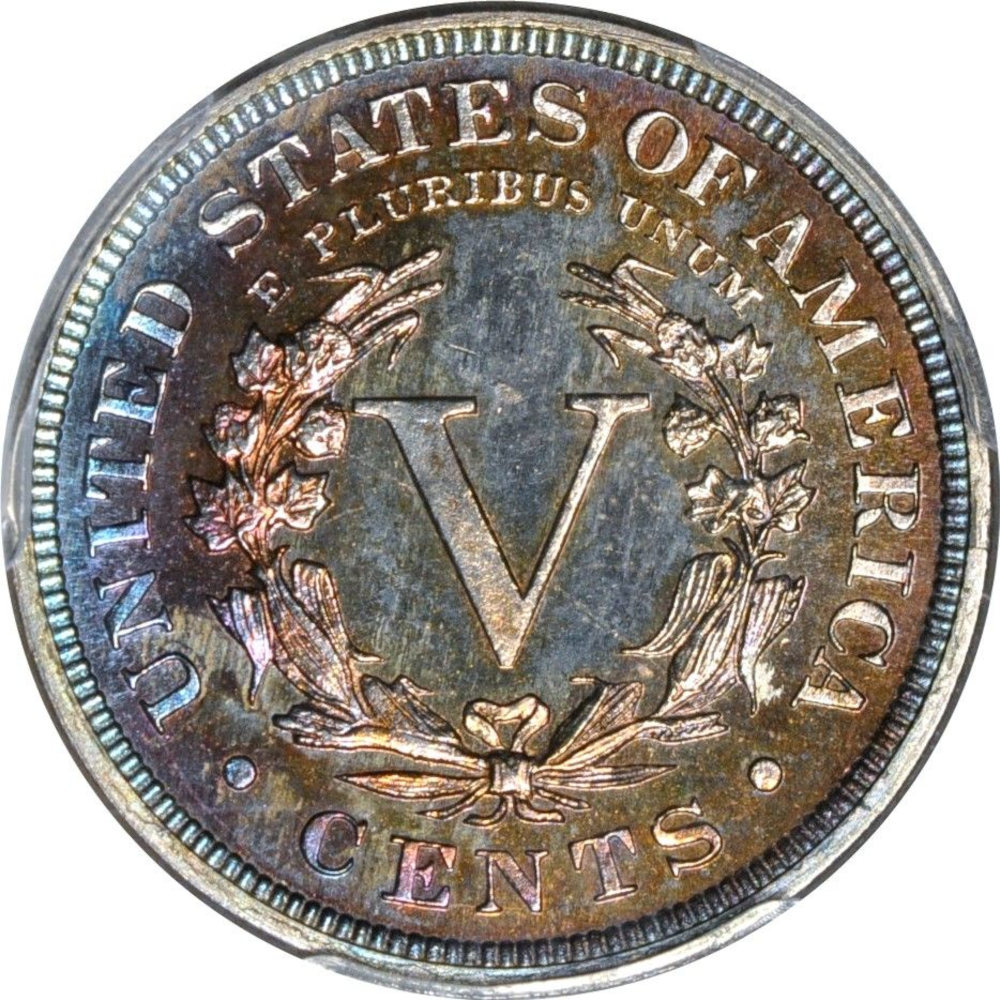

1783 1/2p Nova Constellatio Copper. Crosby 2-B, W-1865. Rarity-2. CONSTELLATIO, Pointed Rays, Small U.S. PCGS MS-62 BN.

Ex Ryder-Boyd-Ford.

136.4 grains. Glossy medium brown with traces of frosty luster. Both sides show excellent visual appeal and bold detail. A little area of discoloration is seen in the area between the wreath and the left side of the date, and some old encrustation remains among the leaves.

Provenance: From the Sydney F. Martin Collection. Earlier from Lyman Low’s sale of January 1908, lot 283; Hillyer Ryder to F.C.C. Boyd; F.C.C. Boyd estate to John J. Ford, Jr.; our (Stack’s) sale of the Ford Collection, Part V, October 2004, lot 35.

From the University of Notre Dame’s Coin Library:

THE AMERICAN COINS OF 1783

Constellatio Nova Coppers: Introduction

In 1783 Robert Morris, who was the Superintendent of Finance during the Confederation, hired the British engraver Benjamin Dudley to design a set of coins for national use. Silver patterns denominated as 1000, 500 and 100 “units” as well as a copper 5 “units” pattern were produced (possibly also an 8 “unit” copper) but were never put into production. As patterns, these items were produced in very limited numbers as examples of what the final coins would look like. The obverse of the pattern coins display rays emanating from an Eye of Providence (as it was known by contemporaries) surrounded by a circular constellation of thirteen stars, as had been used on the $40 Continental Currency bills from the emission of April 11, 1778. The legend on the patterns was in Latin, NOVA CONSTELLATIO (A New Constellation). The reverse of each pattern display a wreath around the initials U.S. with the denomination below, outside the wreath is the legend, LIBERTAS JUSTITIA (Liberty Justice) and the date 1783. For additional details see the section on the NOVA CONSTELLATIO patterns of 1783. The design found on these patterns was the model for the private copper issues bearing the dates 1783, 1785 and a very rare variety dated 1786.

Unfortunately there is little documentary evidence on the private coppers that were based on the Morris pattern, and the few contemporary references that do exist are not in agreement. Even the word order in the name of the coin has been debated, NOVA CONSTELLATIO or CONSTELLATIO NOVA. In a single news item picked up by three different London newspapers during the week of March 11-14, 1786 the coin was said to have been inscribed CONSTELLATIO NOVA. The article also stated the coin was produced by the American Congress; but that information was retracted on March 16th. Apparently, the journalist was confused about the Confederation patterns, produced by Morris in 1783 and the private issue coppers on which he was reporting. Also, the Reverend William Bently of Salem, Massachusetts described the copper coin in his diary entry for September 26, 1787 using the word order CONSTELLATIO NOVA. In 1974 Walter Breen suggested the CONSTELLATIO NOVA word order as the correct form since it was better Ciceronian Latin and was found in contemporary sources. Based on his suggestions most authors adopted that word order.

More recently Eric Newman has shown the Confederation patterns were referred to as NOVA CONSTELLATIO coins in contemporary sources, such as Samuel Curwen’s diary entry for May 15, 1784 where he uses that word order to describe the unique 5 unit copper pattern which was given to him. The word order on the Morris patterns themselves, especially the 500 unit piece, clearly shows NOVA CONSTELLATIO is the correct order. Newman also discovered contemporary references concerning the private copper issues, as the discussion by W. B. inThe Gentleman’s Magazine of October 1786, which used the NOVA CONSTELLATIO word order (on p. 868 and plate 2, between pp. 824 and 825, figure 9).

Although NOVA CONSTELLATIO is surely correct for the patterns, the word order on the private coppers is ambiguous. The word CONSTELLATIO is in the position usually taken to be the top of the coin (based on the location of the eyebrow on the central eye) while NOVA is near the bottom. However, in the illustration to the article in the Gentleman’s Magazine mentioned above, the obverse of the copper (1785 variety) is displayed in what would be called an upside down position (i.e. with NOVA on top) (click here for the illustration). This mistaken orientation may be the reason for the use of the word order “NOVA CONSTELLATIO” in the article. Interestingly, two years later (in December 1788) in an communication from T. W. Lee of Peckleton (on p. 1069) the magazine included an illustration of the 1783 variety as plate 2, figure 4, opposite p. 1069 (named only as a new American coin), this time with CONSTELLATIO on top, but showing that side of the coin as the reverse! (click here for the illustration). Clearly the ambiguity of the design caused confusion, even to contemporary numismatists.

Some varieties (most of the 1785 dated coins) have no punctuation, while others (primarily the 1783 coppers) have a stop between NOVA and CONSTELLATIO and a quatrefoil between CONSTELLATIO and NOVA. The word order depends on which mark one interprets as the starting point, the stop or the quatrefoil. On the 1783 dated coppers, the reverse side has a quatrefoil between the two words in the legend, using this logic for the obverse would give CONSTELLATIO NOVA as the word order. Currently, it appears NOVA CONSTELLATIO was the intended word order; certainly that was the order for the patterns on which the private coppers were based. However, on the private coppers coins the words are placed in such a way that the order is ambiguous. One wonders if the diemakers clearly knew what was being requested. In fact, based on the position of the eye design it appears CONSTELLATIO was at the top and therefore was usually read first, although this was clearly not the intention of Morris and Dudley. Apparently, contemporaries appear to have used both word orders and had difficulty in determining which end of the obverse was up! Furthermore, it appears contemporaries often did not describe the coin in relation to the obverse legend. An article in The New Haven Gazette for May 4, 1786 (also in The Massachusetts Centinel from Boston of May 10, The Connecticut Current of Hartford on May 15 and The Newport Mercury of May 29) described the coin as: “on one side an Eye of Providence, with thirteen stars; the reverse U.S. for United States.” It seems there is no one answer as to a contemporary reading of the legend nor does there appear to be a single contemporary name for this copper.

Much of our information on the origins of this issue is derived from the correction to article originally published in various London newspapers between March 11-14, 1786. The correction was published in The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser for March 16, 1786. In corrected the earlier article which had reported the coins were minted in America by the American Congress. The correction stated:

A correspondent observes, that the paragraph which has lately appeared in several papers, respecting a copper coinage in America is not true. The piece spoken of, bearing the inscription “Libertas et Justitia, & C” was not made in America, nor by direction of Congress. It was coined in Birmingham, by the order of a Merchant in New York, many tons were struck from this dye, and many from another; they are now in circulation in America, as counterfeit half pence are in England.

The author used the term “dye” to refer to a design rather than to a specific die. From existing examples we know there were two basic designs. One design has the date 1783; it appears in three obverse and three reverse die varieties found in three combinations. Two varieties (Crosby 1-A and 2-B) have obverses with pointed rays, while one variety (Crosby 3-C) has an obverse with blunt rays. The reverse of all three coins bear the date 1783, contain a quatrefoil between the words LIBERTAS and JUSTITIA and display the initials US in block letters. The other design has the date 1785 and is appears in five obverse and five reverse die varieties found in six combinations. In this group obverse 1 is the same blunt ray die used as obverse 3 in the 1783 series. Obverses 2-5 have pointed rays and contain no punctuation in the legend. All of the reverses (A-E) bear the date 1785, give the legend as LIBERTAS ET JUSTITIA and display the initials US in an ornate script.

The article clearly states the CONSTELLATIO NOVA (or NOVA CONSTELLATIO) coppers were produced as lightweight tokens. Mossman has discovered the first coppers produced in the series were made at an acceptable weight of 140 grains (this came close to the British halfpenny weight of about 150 grains); but as the series progressed the weight of the coppers was reduced to 127 grains and then 116 grains. However, as there were few coppers available in the new nation, these coins were readily accepted. According to the Joseph Felt’s, An Historical Account of Massachusetts Currency, published in 1839, the predominant copper in Massachusetts in 1788 was the 1783 CONSTELLATIO NOVA.

The dating on these coins does not necessarily reflect the year of minting. Since the first news items about the coins do not appear until 1786, it seems unlikely any coppers had been minted in 1783! In fact, all early descriptions that have specific details which can be linked to a particular variety refer to the 1785 coppers. The first reference clearly referring specifically to the 1783 variety is an illustration to a note on a new American coin in the Gentleman’s Magazine of December 1788. Indeed, Newman discovered some 1783 coppers were not introduced into circulation until about May of 1786. Apparently, the 1783 date was simply copied from the 1783 Morris pattern which had been used as the model for the coinage.

From available evidence it appears the 1783 coppers were put into circulation in America in 1785-1786. Mossman has surmised three varieties of the 1785 token were circulating by late 1786 or early 1787 and that the final three 1785 varieties were circulating before July of 1787. They appear to have circulated in several states but are most often associated by contemporaries with New York.

Gouverneur Morris has long been identified as the “Merchant in New York” who, according to the London newspaper, had commissioned the minting of the coppers. Gouverneur Morris, no relation to Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris, was a Philadelphia lawyer who had worked closely with Superintendent Morris and had actually authored the 1783 coinage proposal (for which the NOVA CONSTELLATIO patterns had been made) that went forward under the superintendent’s name. Gouverneur Morris had been raised in New York City but he was not a merchant and did not reside in the city or the state of New York. This problem, of equating Gouverneur Morris as a New York merchant, was recently brought forward by Michael Hodder who went on to mistakenly suggest Dudley and Morris actually produced the coppers in Philadelphia. In fact, Eric Newman seems to have solved the puzzle. Apparently, the merchant who had the coppers produced was William Constable, who operated a “House of Commerce” on Great Dock Street (now Pearl Street) in New York City. Newman has discovered an agreement of May 10, 1784 in which Robert Morris, Gouverneur Morris and William Constable, “through a mutual Confidence in each other, have entered into a joint Copartnership as Merchants, under the firm of William Constable & Company.”

It appears after the NOVA CONSTELLATIO pattern was rejected by the American Congress, the two Morris’s entered into a private partnership with Constable. They keenly understood the pressing need for small change in America and fully realized underweight coppers could be traded for more that it would cost to produce and import them. In fact, their coinage proposal was put forth as an attempt to stop the British counterfeiters who had been flooding the American economy with poor quality lightweight halfpence. It appears after the defeat of their proposal the two Morris’s decided to become “silent” partners in the firm of William Constable & Company in order to use the coinage design they had created to produce lightweight coppers in England that could then be imported to America and distributed at a profit.

During the second half of the decade of the 1780’s the Republic of Vermont, as well as the states of Connecticut, New Jersey and Massachusetts began producing coppers, which were heavier than other circulating coppers. As these heavier coppers became more plentiful, lightweight coppers as the CONSTELLATIO NOVA tokens (especially the 1785 varieties) were taken out of circulation. In New York, where they were probably most abundant, their circulation was restricted by law starting as of August 1, 1787. As these coins were soon to loose their value many individuals sold them at a discount. Some mints purchsed these highly discounted CONSTELLATIO NOVA tokens in order to use them as a cheap source of finished planchets, illegally restriking them as New Jersey, Vermont, or Connecticut coppers; as occurred at the Elizabethtown Mint in New Jersey, Rupert’s Mint in Vermont, and Thomas Machin’s Newberg, New York facility.

Fifteen examples of these coppers have been discovered bearing the date 1786 (with US in roman letters), which, according to Newman, may represent a counterfeit die or possibly could have been produced by a less skillfull diemaker in anticipation of a further order from America. Additionally, there is a very crudly produced 1785 copper, with the legend clearly being “NOVA CONSTELLATIO” with only twelve rays and twelve stars and a reverse with US in script. This item is generally considered to be an American made counterfeit.

The CONSTELLATIO NOVA tokens were plentiful in America in the years just preceeding the first large scale copper coinage production. By the second half of the decade several mints had opened in the states and in Vermont and several Birmingham firms were producing tokens specifically for American clients. As a successful early condender the NOVA token has an influence on or been affiliated with several other early American coppers. Sometime during the second half of 1785 William Coley of New York designed the first Vermont landscape coppers adapting the Eye of Providence design with the blunt ray from a Nova copper he had seen in circulation (and in 1786 using the Nova pointed ray design). An even closer relationship exists with the British made IMMUNE COLUMBIA coppers, where three of the CONSTELLATIO NOVA dies (1783 Crosby obverse dies 2 and 3 and from 1785, obverse die 3) were combined with the two known IMMUNE COLUMBIA reverse dies to produce this privately made issue for circulation in American. Further, Mike Ringo has discovered some of the letter and number punches used on the 1783 Nova die 1-A (which is the die thought to be by a different diemaker) were also used on the 1783 dated GEORGIVS TRIUMPHO copper.

References

See: Eric P. Newman, “New Thoughts on the Nova Constellatio Private Copper Coinage” in Coinage of the Confederation Period, ed. by Philip L. Mossman, Coinage of the Americas Conference, Proceedings No. 11, held at the American Numismatic Society, October 28, 1995, New York: American Numismatic Society, 1996, pp. 79-105; Michael J. Hodder, “More on Benjamin Dudley, Public Copper, Constellatio Nova’s and Fugio Cents” The Colonial Newsletter 34 (June, 1994, serial no. 97), 1442-50; Mossman, pp. 193-196 and Breen, pp. 117-119, also Walter Breen, “CONSTELLATIO NOVA” The Colonial Newsletter vol. 13, no. 3 (September, 1974) serial no. 41, pp. 453-455; Tony Carlotto, “1786 Nova Constellatio Census,” The C4 Newsletter, A quarterly publication of the Colonial Coin Collectors Club, vol. 6, no. 3 (Fall, 1998) 43-46.